|

| /Mashable |

Fifteen

years ago, American Sniper would have

won Best Picture.

That

may be a tad premature, but it’s safe to say that in the last decade or so, the

Academy has moved far away from the very public who’s watching and betting on

its awards. As Sam Adams writes in Criticwire, the 2015 Oscars are really the

first to ignore big-budget spectacle right down to the technical categories,

which were dominated by a Wes Anderson film and a Sundance jury prize winner.

Last year, Gravity – a box office as

well as critical sensation – cleaned up below-the-line. Movies that tend to

make a lot of money usually do.

But

this year, the Academy handed just a single sound editing award to American Sniper, a lone visual effects

trophy to Interstellar and nada to

multi-nominee Guardians of the Galaxy.

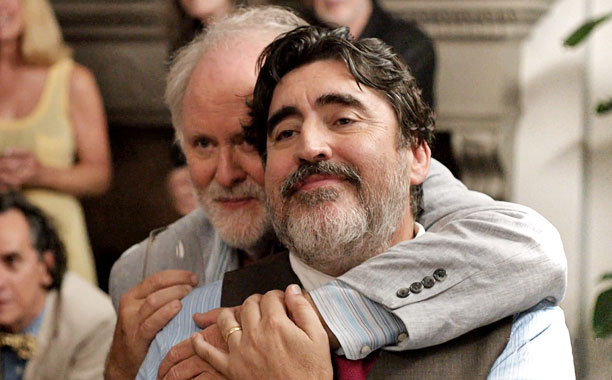

They were trounced principally by The

Grand Budapest Hotel, which ironically then fell in major categories to an

even-less-commercial pic in Birdman.

It’s no secret that, just as the culture of movie-going has changed over the

past five years, the Academy seems less inclined to meet the public in the

middle. And for what it’s worth, American

Sniper found more favor with critics than some blockbuster late 1980s-1990s

Oscar champs like Driving Miss Daisy or

Titanic.

If

you look at the winners from 1988 right until 2003, only two movies won with

less than $100 million made domestically: Braveheart

and The English Patient, a pair of

war films that hit their emotional beats with forceful, ripe-for-awards

intensity. Since 2009, however, only two of six winners have made over $60

million: The King’s Speech, which

perhaps falls in the category of The

English Patient’s, and Argo, of

which I’ll have more words on in a minute. Birdman,

this year’s winner, has grossed under $40 million, a fair number below even

last year’s 12 Years a Slave.

But

what’s interesting about the choices made by the Academy is that they are

completely self-reflective. Yes, they have moved away from the public

consensus, but they still remain reluctant to embrace critical darlings. If we’re

using post-2009 as a timeline, Oscar has touched on the critics’ choice only

twice, even as films like The Artist

and Birdman grossed low numbers. And

in both of those years, the Academy had a chance to make history that was less

triumphant than respondent to a “You better…” sentiment. In 2009, Kathryn

Bigelow became the first female director to win Best Director and to be behind

a Best Picture winner (The Hurt Locker).

And in 2013, despite a more-profitable and equally-celebrated film in Gravity as a rival, 12 Years a Slave presented the (sadly) first opportunity for a film

with a black director and predominantly black cast to win Best Picture. Again,

both of these films deserved it – but that’s hardly what we’re talking

about when it comes to Best Picture winners, right?

Of

course, in relative terms, The Artist,

Argo and Birdman all earned good reviews as well – one could reasonably call

them “meet in the middle” choices. The

Artist may have been the third-lowest grossing of all nominees, and Argo may have been less-preferred than Lincoln or Zero Dark Thirty (among possible winners; otherwise, Amour could be included) by critics, but

they’re not incomprehensible choices. But these films fit into an Oscar anomaly:

their messages – so intrinsic to the qualities of a Best Picture winner – are driven

by their being situated in the world of movies and the industry. It’s safe to

say that as Birdman hurled vitriolic sentiment

at critics and established an emotional center within a comeback story, it

cumulatively possessed a narrative voters could get behind. The Artist was deeply, powerfully

nostalgic. And Argo – well, according

to Ben Affleck’s historical drama, Hollywood got us out of the Iran Hostage

Crisis. Argo beat a far more

political (and acclaimed) film in Zero

Dark Thirty, as well as a more elegantly-composed and politically-astute

one in Lincoln. The Artist had an absurdly thin slate of films to compete with, but

even so, equally-acclaimed movies from long-respected directors like The Descendants and Hugo grossed nearly twice as much, and didn’t stand much of a

chance.

This

is all important information because, without question, the nation’s

relationship to the Academy Awards has shifted. Popular movies aren’t winning

anymore – and even the popular ones like Argo

lack staying power. They’re not part of a cultural moment, nor do they

provoke conversation, nor are they anything close to “masterpieces.” Boyhood, as uncommercial as it may have

been, has that lasting power, not to mention an overwhelming critical consensus

behind it. A leading 31% of 50+

surveyed critics chose Boyhood as

the deserving winner; Birdman snagged

just 16%, also far below The Grand

Budapest Hotel’s 27%. And as for public preferences, American Sniper claimed an overwhelming 38% in a CBS

poll, whereas Birdman tied with Boyhood at a mere 17% apiece.

As

most recappers of the night have already documented, social media was surprisingly,

vocally dissatisfied with the selection of Birdman.

With excellent reviews and a lot of hope in the chances of its leading man

Michael Keaton, Birdman winning to

such a negative reaction is both odd and illuminative. The sentiment does not

go “Oh please, that movie was terrible” – nor does it say, “Jesus Christ, no

one even saw it.” What we’re hearing is a general frustration as to what the

Academy is doing at this point. For the third time in four years, the

industry has awarded a movie about itself. There were movies that earned more

acclaim and more money – in most cases, at least one achieved both – but Hollywood,

intentionally or not, has consistently been making inward-focused choices. I

think Birdman is a hell of a lot more

deserving than American Sniper, and I

think Boyhood takes the cake both in

artistic and historical value, but Birdman

makes the least sense of the three as an Academy Award selection. Or maybe “sense”

is the wrong word – it’s the least potent choice.

This

is not a conversation surrounding a movie that just barely eked it out. Despite

the fantastical predictions of pundits and critics (this one included), Birdman had this in the bag. It swept,

with Alejandro G. Inarritu beating Richard Linklater for Best Director and Wes

Anderson for Best Original Screenplay. It won handily. We’re getting in the

habit of dubbing these races a lot closer than they are, and that’s because for

the most part, the Oscars roll on for three-and-a-half hours in depressingly predictable

fashion. Seeing as BAFTA and SAG have crossover membership with the Academy,

when Eddie Redmayne, Julianne Moore, J.K. Simmons and Patricia Arquette all win

with both groups (and more, including the Globes for each), it’s safe to

conclude that they’re going to win. And they did. As audiences continue to

segment, the Academy Awards represent a rare instance for the nation to gather

around the television (and on their iPhones) live. The irony is that what we’re

watching is an excessively-predictable march to a love-fest for a film rallied

around by neither critics nor the public. And, to be clear: Birdman was the favorite movie of the

year of many. But looking at the list

of critics aggregated by Metacritic alone, eight other films were named the

Best of the Year by at least four publications. Taste is taste, and for any

interesting conversations to take place, there should be many favorites chosen

individually.

The

Academy Awards are not a critics’ circle, nor are they the Peoples’ Choice

Awards. They are, absolutely, their own body. But it’s unclear what they are

representing – especially considering the proclaimed historical and

nationalistic value they hold onto so dearly. Watching the Oscars has become a

mix of resigned pleasure for the deserving winners we already knew would win; surprise

only at musical performances and speeches that strike a nerve (this year, Lady

Gaga and John Legend/Common); and irritation at just about everything else. Why

are we all watching – what are we holding onto?

Fifteen

years ago, we’d probably be seeing American

Sniper take it home. Not only did it spark a national debate, but it

rallied liberals and conservatives alike, and is certainly reflective of our

moment in time. Because the Oscars never have been (and never will be) a

barometer of quality, that the “zeitgeist” element of the awards has been all

but stripped – or at least, is absent far more frequently than before – is damaging

for their cultural relevance and value. Qualitatively, the Academy’s choices on

average have probably improved. But they’re also far less relevant,

near-opposed to what’s making a dent in the culture.

I’d

argue that for the Academy to build on the strides made last year by honoring 12 Years a Slave, they would need to

have recognized Boyhood: it’s a film

of groundbreaking artistry (in short, by situating resolute realism on an epic

scale) and nationally-recognized value. Birdman

doesn’t provoke anything deep: its historical value will certainly be

short-lived, and it represents Hollywood yet again turning towards itself in a

muddled year of competitors.

At

their best, the Oscars are a reflection of a moment in time, whether

artistically or publicly. But Birdman,

liked by most and loved by some, reflects

on neither. Put it this way: it’s not a Forrest

Gump, but it’s not a Deer Hunter

either. It is a movie for Hollywood. In the last six years, the industry has

rewarded great movies when they needed to (Hurt

Locker; 12 Years), and good

movies when they wanted to. What is missing, then, is a public acknowledgment –

a sense of the culture at large. Movies tell us who and where we are, and the

Oscars used to reflect that more often than not. They told us that Titanic would be the enduring, cheesy

love story of our times, or that Lord of

the Rings was so good that their fantasy bias could be overcome. But Birdman, like The Artist, Argo and many

future winners, only tells us that Hollywood loves to see itself in the mirror.