Finally having seen enough to compile my list, below are my top 20 films of 2014. I've ranked the top 10 in order (with a tie, so I guess 11), with six runner-ups discussed in alphabetical order, and the three that round out the top 20 also briefly noted.

Of course, many movies I saw in 2014 didn't make this list. Five that I quite liked but found flawed are discussed here, in the context of a single scene. But otherwise...

Some

have been shortlisted by many other critics. Jean-Marc Vallée’s Wild is smart but nonetheless fell flat

for me, far outdone by John Curran’s Tracks.

Citizenfour and Life Itself were fantastic documentaries – I’m that rare person

that prefers the latter – but unlike the form-bending and emotionally-wrenching

The Act of Killing and Stories We Tell last year, their role as

films didn’t quite outrank my favorite narrative features. Listen Up Philip started out savvy and salty, but deflated by its

third act – seek out a better under-the-radar indie in Lucky Them, as low-key and familiar as it is astute and well-acted.

In a year of stellar debuts – Chazelle’s Whiplash,

Kent’s Babadook, Gilroy’s Nightcrawler – Justin Simien’s Dear White People impressed with its

ideas, but its execution was relatively freshman. Interstellar, its substantial technical merit in mind, tells a

preposterous story without enough oomph. American Sniper is a thinly-drawn superhero movie masked as a morally-minded war movie. And, apparently, I’m the only critic

around that didn’t fall for Ida – its

deliberateness left me cold, even as I admired its confrontational narrative

and lush cinematography.

And

some words on a few “awards” movies; the prestige November-December glut. Still Alice is a mediocre movie that

features one of the year’s best performances – and The Theory of Everything is a mediocre movie featuring a pair of

them. Big Eyes is fine, but it’s

messy and wastes its potential. Into the Woods works sometimes, but director Rob Marshall can't quite bring it together. Unbroken

is the Best Picture of fifty years ago; in 2014, it’s painful to sit through,

going to places we’ve already been without an accompanying reason. The Imitation Game, however, is

surprisingly solid, chastised for its very existence even as it fashions an

intelligent narrative and a sharp style. Beyond these, as always, many movies

favorited by Oscar and other voting bodies happened to be excellent, and are

featured below. Of the rest, I either haven’t screened them just yet, or, more likely, I don’t feel the need to document their absence

(I liked you more than I expected, Begin

Again; I’m still disappointed in you, Monuments

Men).

Last year, the best

film of the year was Steve McQueen’s 12

Years a Slave – my other favorites

were the aforementioned Act of Killing

and Stories We Tell, along with (in

order) Her, Blue Is the Warmest Color, Nebraska,

American Hustle, Short Term 12, Gravity

and Enough Said – and this year it’s Boyhood. For me, this is an unequivocal

choice, and hopefully the reasons I lay out below sufficiently explain why.

On to the Best 20 Movies of 2014 (starting from the top, for once!)...

1) Boyhood – Richard Linklater

The

first time I watched it, I was impressed. How could I not be? How did

Richard Linklater do that? But I didn’t want to be too easy on it. And so, I gave

it a second viewing, two days before Christmas, with my family. The takeaway:

sometimes, judging art purely on how it affects us and makes us feel is okay.

With Boyhood, the specificity of its

story renders its ideas and characters universal and potent. Linklater’s touch

is simply magical. In this epic devoted to growing up, whether into

adolescence, adulthood or middle-age, nothing is simple and yet everything is there.

Linklater's portrait is comprehensive, full, intimate: he captures how we identify change

and growth through the innocuous and mundane. When dad sells his car, you feel

it – you feel him changing, you learn of the congruence of objects and ideas overtime.

When mom goes through yet another disastrous marriage, it hits you hard – that

idea is internalized that sometimes, for some people, you can never really

figure it out.

Linklater’s

script is just perfect, giving equal weight, attention and respect to his

subject Mason (Ellar Coltrane) as he unknowingly punishes his mother as a 13

year-old, or esoterically rambles as he approaches college. You’ll cringe at

his rant on “people say they don’t care about what people think, but they do!”

but you’ll recognize it – you may have even given the same speech. In this way,

Boyhood is a holistic identification of how we come to see and learn about the world. It’s also a

specific and humane conveyance of adulthood. Despite getting married and

settling down, Ethan Hawke’s artistically-minded and sporadically air-headed

father remains easily distinguishable. Despite finding a purpose and a

vocation, and raising two great children, Patricia Arquette’s mother is still

disappointed – “Is this it?,” she cries to her son at the end of the film.

Linklater

has demonstrated a keen understanding of people before – it’s his very appeal.

But in Boyhood, he takes them across

a decade, allows them to change and grow, and still keeps the imperfect spirit

of who they are. I watched my mom’s eyes as the movie played for me a second

time, welled and so deeply touched. It’s how I felt too – I grew up

differently, but I recognized it all, feeling and coming to understand the

world through my parents as Mason did his. There are so many empirical reasons

why Boyhood is great – its vibrantly

authentic dialogue, its scope, its bone-deep performances – but it’s my best

movie of the year because of how it made me feel, watching with the people I

grew up with. That’s what art is supposed to do – probe us, affect us,

challenge us. Boyhood took me back

and thrust me forward. It startled me. It moved me. And, on that second

viewing, it broke me. It’s a breathtaking achievement, and a film that is, at

this moment, very close to my heart.

2) Leviathan – Andrey Zvyagintsev

Andrey

Zvyagintsev’s Leviathan is a

devastating social parable set in contemporary Russia. Its origins are biblical

and philosophical, confronting with piecing naturalism the Social Contract that

exists between Russian authority and its citizens. But Leviathan is not an overt, politicized piece of work – rather, it

stuns with its intimacy. It depicts relationships and characters, in a world in

which their fate is not theirs to choose, and allows us to recognize them and connect

with them. There’s biting, deep humor here, along with painful domestic

conflict. But the exterior is lavish, considering God’s justice and Russian

politics with a critical eye. These characters fall and their relationships

crack, inevitable in such an inescapable system. Zvyagintsev’s societal criticism

is rendered that much more potent as a result of his character-centric approach: with a principal focus on what extraordinary circumstances do to ordinary

people, Leviathan is a true, aching

tragedy.

3) The

Grand Budapest Hotel

– Wes Anderson

With

The Grand Budapest Hotel, Wes

Anderson uses the very specificity of his style to tell a story of greater

scope than he ever has before. In this

narrative-within-a-narrative-within-a-narrative, the director maintains his

commitment to color scheme – this time, purples, reds and yellows – and brings

back his company of actors and set of miniatures in the process. But the

expression here is sharper, deeper and bigger – yet still just as infectious.

The Grand Budapest Hotel

is an idyllic work of art for the way it blends an artist’s worldview with such

all-encompassing, well-trodden ideas in storytelling. This is a film about the

way we tell stories, about the role of war, about changes in culture and mores

across time – and as expressed through Anderson’s rigid camerawork and manic

sense of humor, it’s just brilliantly, memorably different.

4) Mr.

Turner

– Mike Leigh

The

pervasive problem with biopics is their inability to cinematically identify and

grapple with their subject(s) work – with one big exception in Mike Leigh’s

filmography, first with Topsy-Turvy

and now Mr. Turner. Here, in his

recounting of 19th Century British painter J.M.W. Turner’s later

years, Leigh finds a way to answer that subjective question: how does an artist

see the world? His camerawork is less an effort in moviemaking than a sequence

of paintings, capturing the world in all its detail – often breathtakingly

beautiful, sometimes lightly disturbing, and occasionally morbidly funny – with

expansive splendor. His subject, portrayed superbly by Timothy Spall, is gruff

and socially inept, mining humanity and perspective through the world’s natural

tableaux. Leigh’s confidence, laying out details of Turner’s life without

judgment or overt exposition, allows his subject to just be. He contends with

the individual and the work in a way I’ve seen few filmmakers capable, and his

dialogue remains as sharply characteristic as ever. As I wrote in my review, Mr. Turner is not a masterpiece: it’s a

series of masterpieces.

5) Two Days, One Night –

Jean-Pierre Dardenne & Luc Dardenne

Two Days, One Night

tackles contemporarily-focused ideas about class, decency, sacrifice and self-worth

with unwavering realism. Its conceit practically gives away its thematic value

and narrative progression: Sandra (Marion Cotillard) must visit with each of

her co-workers, and ask them to forgo their bonuses so that she can keep her

job. She steps into the lives of the generous, the entitled and the struggling –

with each visit shakily lensed in a single-take, progressing in

documentary-like fashion. The evocation is mammoth. Cotillard acquits herself

astonishingly well in a performance that requires so much to go unsaid – her stilted

walk, her timid eyes and her quivering mouth convey what words cannot. And the

film, so raw and honest in its intricate depiction of humanity, makes a vital claim

for decency and humility. Stripped of visual tricks and musical composition,

the Dardenne Brothers manage once again to deliver a stirring piece of

humanist cinema.

6) Selma – Ava DuVernay

Ava

DuVernay’s expressive, sweeping Selma

is directly antithetical to our expectations of historical drama. Rather than overloading

with notes and factoids, the director exhibits striking confidence in her

camera and her actors. A still image of silent protestors will fade into a gentle

tracking shot, of millions marching for the right to vote. The camera will stay

soft and fixed for minutes at a time, in a room with Martin Luther King (David

Oyelowo, brilliant) and his wife Coretta (Carmen Ejogo), completely comfortable

in silence and deep emotion. This is Selma’s

indispensability. It tackles and confronts history, but hands its story to the

people: a flawed leader, a unified community, an activist spirit. Its

contemporary relevance is steeped in that unconventional approach, in the way

it so generously and fully identifies the role of community and solidarity in

fighting something larger than oneself. Moving, complicated and startlingly

realistic, Selma is the historical drama

we’ve long been waiting for.

7) Inherent

Vice

– Paul Thomas Anderson

Inherent Vice

is a sublime concoction of zany romantic nostalgia, as only director Paul

Thomas Anderson could envision and pull off. His adaptation of Thomas Pynchon’s

book of the same name is admirably faithful, and yet totally his own – it’s a

spotty, incoherent detective story that makes magic moment-to-moment,

cameo-to-cameo. It’s not totally funny nor especially heavy, and yet it

possesses a vitality and spark rooted in its point-of-view and enchanting

idiosyncrasy. Obviously, this is a filmmaker of considerable talent, but here

he underscores a colorful collection of scenes with levity and perspective,

mourning for a time and a community changed and vanished. The comedy

and cast – highlights include Martin Short as a lunatic dentist and Jena Malone

as a drug-addict loner – draw attention and provide Inherent Vice with its substantial entertainment value. But tuning

in to what Anderson has to say, and gazing in awe at the mastery with which he

communicates it, is the film’s unexpected treat.

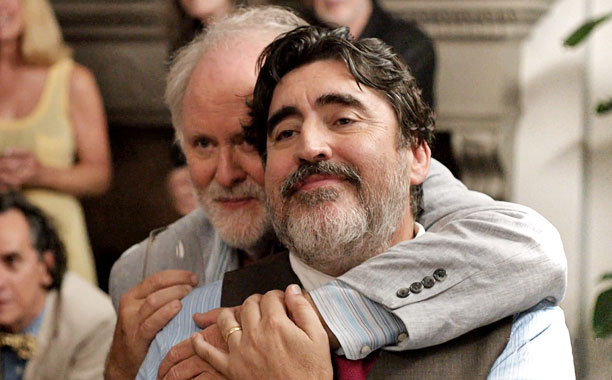

8) Love

Is Strange

– Ira Sachs

It’s

hard to believe that Ira Sachs, fresh off the sexy and dark (and flawed) Keep the Lights On, could so sharply

turn a corner with Love Is Strange

and do it so damn beautifully. Ostensibly confronting the perpetual complications

of gay marriage in America, the bigger and impassioned idea here is an exultant

ode to love and commitment. Sachs’ focus on the enduring love of an elderly

couple, played by Alfred Molina and John Lithgow in career-best performances,

eventually extends to the ongoing struggles between married people of

middle-age, and to a teen’s reluctance in pursuing his first crush. Treasured

are the stories that just hit you, that move you – Love Is Strange is exactly that. It’s freewheeling, as loose and

unrefined as life. It’s sad, acknowledging the inevitability of loss with

grace. And it’s timeless, explicating the complicated role that love plays in

our lives, young and old, and demonstrating its wondrous eternality as a

result.

9) Force

Majeure

– Ruben Ostlund

In

terms of sheer intelligence, few 2014 works were as effectively brainy as Ruben

Ostlund’s Force Majeure.

The film posits the role of men and women, generation by generation, in a

changing world. A freak incident – a “force majeure” – leads to ninety minutes

of husbands, wives, boyfriends and girlfriends arguing incessantly and

senselessly. By its conclusion, the movie’s methods of communication – from the naturalism of the

performances to the oblivion-like elicitation in the cinematography – just blew

me away. It situates a traditional family up and away in a ski resort, and

aggressively introduces them to new ways of thinking, pushing them to reflect

on who and what they are. In wrestling so naturally with modernity, gender,

family and aging, Force Majeure

viscerally (and hilariously) exposes the absurdity of the human condition.

10T) The

Babadook –

Jennifer Kent

This

stunning, wholly unexpected conception of parental rage and suppression ranks

as the year’s best debut. Ms. Jennifer Kent inverts the approach taken in

horror film to create a devastating cinematic opera – the tired trope of the

demonized mother is taken literally, as Amelia’s (Essie Davis) tormented core is

fashioned as an ethereal monster called “The Babadook.” Kent’s control here is astonishing,

presenting a chillingly frightening vision while never wavering in the complex focus

on motherhood and repression. The conveyance here is overtly feminist, providing

its protagonist with uncommon agency as a sexual being and anguished griever –

and yet, the viewing experience is both completely engrossing and beguilingly innovative.

By so fully succeeding in balancing the tragic with the scary, this production

is an across-the-board class act – though it’s Ms. Davis’ fearsome performance that

makes it all work so well, going to a plethora of emotional places with

fearsome commitment.

10T) The

Immigrant

– James Gray

The Immigrant

is an uncompromising cinematic experience. Director James Gray revels in

melodrama and classicism, evoking a tragedy of profound feeling that’s both

distinctive and rare for the way it wears its heart on its sleeve. The film

chronicles the plight of Marion Cotillard’s helpless Polish immigrant; Gray

observes her downfall with unsettling sincerity, and lightly albeit intently

acknowledges the corruption and amorality that surrounds her. Of course, this

“corruption” is directly representative of the time, feeding into the film’s

dark interpretation of the American immigrant experience as well as its

broader, nationalistic implications. As Cotillard digs so fearlessly into her character’s

desperation, The Immigrant is a heavy

watch, sad and unabashedly tragic – and yet, bleak as it may be, this is a

beautiful and impressionistic piece of cinema, emotive and connective quite

unlike anything this year.

Six Runner-Ups:

Foxcatcher – Bennett Miller

For

all the talk surrounding the cold and collected auterism of Gone Girl, it’s really Bennett Miller’s Foxcatcher that sustained a mood of

shaky unease better than anything else this year. If Gone Girl wandered aimlessly, Foxcatcher’s

shoes were superglued to the ground. In this pointed conflation of American

masculinity and patriotism, a trio of actors playing against type – Steve

Carell, Mark Ruffalo, Channing Tatum – brilliantly immersed themselves in

Miller’s immaculately-controlled vision. This is unrelenting cinema, willing

you to dive into its world of ever-looming tragedy. With his latest, Miller

remains fascinated by basic conversation – between a storyteller and a murderer

in Capote; an old-fashioned

ballplayer and an academic statistician in Moneyball;

and a wealthy, creepy ornithologist and an undervalued, boorish wrestler in Foxcatcher – and continues to expose

American men and their relationships at their rawest, with a quiet and brutal

intensity.

A

Most Violent Year

– J.C. Chandor

Through

his early years as a director, J.C. Chandor has been experimenting with form. Margin Call was admirably

claustrophobic; All Is Lost felt

boundless. A Most Violent Year

borrows from both, keeping within a city breeding violence as its protagonist

goes after a piece of land located on the water, where he can expand and bring

in the whole world. But the film’s great achievement is taking on a timeless

idea – the paradox of the American entrepreneurial spirit – and spinning it

attentively and originally. Chandor is an especially thoughtful storyteller,

understanding with necessary nuance the relationship between those above and

those below, and the ways in which those at the top perpetuate – and yet are

mired by – decay. In refreshingly condemning violence by exposing its horror

and its roots, A Most Violent Year is a film of unnerving relevance and visual

intelligence.

Obvious

Child

– Gillian Robespierre

This

summer surprise withstood a vast slate of flashier fare to stay in memory. Adapted from director Gillian Robespierre’s

short film, Obvious Child is that

“abortion” movie that infiltrated headline space simply for confronting such a

subject with considered authenticity. But it’s much more – chiefly, a

buoyantly enjoyable comedy unafraid to tread the less-respected terrain of

gross-out humor and cutesy romance. Jenny Slate is revelatory in the leading

role, bare and vulnerable and yet exuberantly comedic, as few are in

contemporary movies. On television, Lena Dunham has effectively subverted

lowbrow comedy, and Mindy Kaling the romantic comedy – Ms. Robespierre’s great

triumph is her reclaiming of those tropes for the movies, in a fashion both

effortlessly feminist and consistently funny. There were bigger movies than Obvious Child in 2014, but few were as gratifying.

Only

Lovers Left Alive

– Jim Jarmusch

After

enduring a half-decade’s worth of Hollywood obsessing over vampire romance, Jim

Jarmusch’s mellow and contemplative Only

Lovers Left Alive arrives as distressingly unique. How, between Twilight and True Blood and The Vampire

Diaries and everything else, has no one actually dealt with the passage of

time vis-à-vis centuries-old vampires? Intimate, intelligent and raucously

retro, Mr. Jarmusch’s accounting of a bohemian vamp romance is a moody foray

into humanity’s cyclicality and art’s durability. Tilda Swinton and Tom

Hiddleston do great, understated work as the couple in question, and Mia

Wasikowska explodes in an against-type turn as a misbehaving little (albeit

still some-hundred-year-old) sister. Through Jarmusch’s characteristically

spooky and musical lens, Only Lovers Left

Alive tackles change and time with a soothing soundtrack and a world-weary perspective.

And by texturing barren Detroit and familiar family dynamics in a most

Jarmusch-ian template, the finished work erupts as both liberally observed and

artistically vibrant.

Tracks – John Curran

Did

everyone forget about this movie? John Curran’s absorbing Tracks is an understated exploration of isolation and outcast-ism. In following Robyn Davidson’s

(Mia Wasikowska) trek across the Australian outback, it’s a reclamation of

humanity, of one’s ability to find that elusive sense of self when surrounded

by nothing but the world. Unlike the connect-the-dots method of Wild, Curran opts not to give us the how

and the why. Robyn simply goes on. The

versatile Wasikowska strips herself of vanity and pretension, beautifully conveying a sense of loss and displacemen. Tracks may use verbal exchanges sparingly, but it’s richly

communicative and comprehensive, with sprawling cinematography and a complimentary

score aiding in the melding of big and small, humanity and nature, peace and loneliness.

Whiplash – Damien Chazelle

In

a year of audaciously confident debut features, Mr. Damien Chazelle’s kinetic Whiplash still manages to stand out. It

moves at an ever-quickening pace, managing to ratchet up the tension and effectively

close in on its abusive mentor-mentee relationship in the process. Here’s a

movie that thrillingly figures it out on the fly – undercooked side stuff

aside, Chazelle’s work is wholly compelling by the time he reaches the final

act, in a sequence so tight and frightening that it puts bigger-budget

heart-racers to shame. The performances from Miles Teller and J.K. Simmons are

big, bold and bloody, and Tom Cross’ editing is as taut and suspenseful as just

about anything released this year. There’s a lot to like in Whiplash, but it’s the alternately

spellbinding and exhausting theatrical experience that makes it something truly

special.

And the final 3...

Birdman

or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance):

Alejandro González Inarritu’s awards darling is a ravishing exercise in

technical virtuosity. Not as deep as it thinks it is, but it’s got a splendid

cast and is seriously entertaining.

Nightcrawler: A taut Los Angeles noir, featuring a crazy-good Jake Gyllenhaal. One of the year's better-crafted thrillers, even if it squanders some thematic potential.

Starred Up: A propulsive, enthralling Irish prison drama, featuring blistering performances from Jack O’Connell and Ben Mendelsohn. One of 2014’s most unsung films.

Starred Up: A propulsive, enthralling Irish prison drama, featuring blistering performances from Jack O’Connell and Ben Mendelsohn. One of 2014’s most unsung films.