This was

an exceptional year for film. Unlike in 2013, however, most of my favorites did

not make the Oscar shortlist. This was my first year reviewing movies, and I

have to say that – at a time when the most talented storytellers are being outsourced into the now-illustrious television – filmmakers are giving us more reasons to attend the

cinema. There really is nothing like sitting in a theater, with other people,

with maybe a some popcorn (I had my fair share this year.)

You

might notice that this is a LONG piece: feel free to skip to the summary

nuggets of my criticism towards the last paragraph. But I really wanted to

review the movies that I didn’t get a chance to review because of this late-budding urge I had. This is my critical time capsule, to remember

why it is that these movies worked so well for me, because – maybe in two years

time – I won’t remember the specifics. And this was a revolutionary year for filmmaking, a

year that truly pushed the borders of storytelling.

Here’s

my 2013 list:

1. 12

Years a Slave

2.

American Hustle

3. Blue

is the Warmest Color

4. Her

5.

Stories We Tell/The Act of Killing

6.

Enough Said

7.

Nebraska

8. Short

Term 12

9.

Gravity

10. Blue

Jasmine/Philomena

And here

begins my 2014 list:

10. The Immigrant (Tie)

Though

a box-office bomb, The Immigrant managed

to ravish, dazzle and mystify in a way few movies did this year. This strange and

macabre voyeur through 1920’s New York tells the story of Ewa (Cotillard), a Polish immigrant taken under the wing of pimp Bruno (Joaquin Pheonix). She is rejected by her American family; she has no one else to turn to except Bruno, and is manipulated into being one his show

girls, an exotic mistress in a sexy Lady Liberty costume. God’s eye is on every sparrow,” magician Emil (Jeremy Renner)

tells her, in love and hopeful that he might protect her from Bruno's unrelenting grasp and rescue her sister from deportation. Bruno - rife with jealousy, fearful of losing his prize - kills him, however, drawing Ewa further into his bind.

Pheonix and Cotillard are doing excellent work here, expanding their repertoire of already impressive material (including Cotillard's collaboration with the Dardennes, a year best performance). James Gray's writing and directing is at once stunningly atmospheric and deliciously melodramatic, a slow-burn examination of the

American institutions that glamorize and perpetuate female bondage. It's arty, cerebral and really creative. A truly well done film.

10.) Whiplash (Tie)

Whiplash is Damien Chazelle’s

feature debut, a film with the startling pace of a horror movie. It’s about music and the drive for perfection; unlike Black Swan, however, its intensity is always grounded in a recognizable humanity. The story is based on Chazelle’s own experience at Julliard, and the familiarity and confidence he brings makes Whiplash,

not simply one of the best first-feature debuts of the year, but one of the

best films of the year, period.

Miles

Teller and J.K Simmons are a ravishing pair. JK

Simmons, a technical virtuoso

with both the snarling bite of an attack dog and the sociopathic smile of a

Cheshire cat, is simply sensational and terrifying. Teller bleeds, sweats and drums like a victimized animal, fighting for his

life, his soul and his art, letting go of all that matters to him to pursue his goal of being the best. While

the narrative is not as tight by the third act and the tertiary characters –

the Dad, the girlfriend – don’t complement the main plot in the way Chazelle

might have intended, Whiplash, nonetheless, is a roller-coaster ride, one that I

wouldn’t hesitate to ride again and again.

9.) Foxcatcher

Foxcatcher is disturbing in its

portrayal of masculinity. If one image from this film

endures, it is John Du Pont (Steve Carrell) looking at the wrestlers he has brought together, having fun and basking in a camaraderie, yet feeling separate and desperate in his attempts to integrate himself. The movie is also very much about the abuses of power: Du Pont takes Mark Schultz under his wing, laughs with him and then, afterwards, Du Pont insults him by calling him monkey. It is sudden, but it reflects the sociopathy of the accumulated wealth John Du Pont has acquired. The brooding nature of repression haunts every image, from the stuffed birds, to the frigid and green landscapes of Foxcatcher farms.

Many (I'm not citing, but many reviews indeed did) unfairly criticized it for skirting over the topic of homosexuality. But Miller uses his masterful cinematic eye to suggest a sexual repression so buried and desperate, it can only culminate and end in tragedy. Set in a time before Reagan acknowledges AID’s, this bristly morality tale reminds us what lies underneath the façades of American masculinity.

Many (I'm not citing, but many reviews indeed did) unfairly criticized it for skirting over the topic of homosexuality. But Miller uses his masterful cinematic eye to suggest a sexual repression so buried and desperate, it can only culminate and end in tragedy. Set in a time before Reagan acknowledges AID’s, this bristly morality tale reminds us what lies underneath the façades of American masculinity.

Mark

Ruffalo does his finest work, breaking down in front of the John Du Pont documentarian, when

he refuses to call him his hero. Tatum, as well, is fiercely committed to

his desperation and angst. Carrell is excellent as well, navigating Du Pont's psychosis with ease and

grace, showing a refreshing sense of discipline and control. These are all

actors working at the top of their game, playing really well off of each other. Bennett Miller gives us a fascinating character study, an impeccably

crafted film and the most refreshing and original takes on American masculinity this year (and this, to be mean, is meant to actively target A Most Violent Year, which did not do nearly enough as I thought it would).

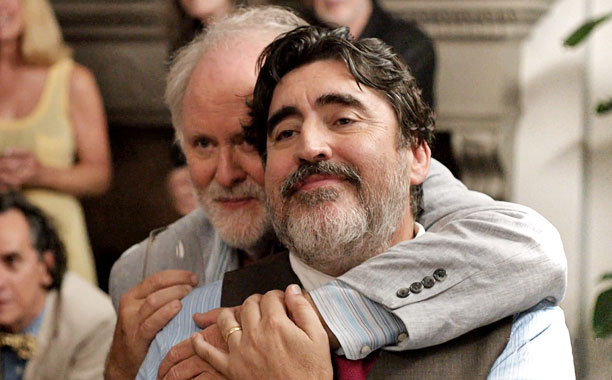

8.) Love is Strange

In

an impressive year for gay cinema, Love

is Strange stands out from the rest. Though his previous film Keep The Lights On suffered from a loose

focus, strongly indicated themes and a melodramatic execution (it was superbly

acted, though), here Sachs never rings a false note, achieving a

disciplined balance between melodrama and comedy, allowing his actors rather

than his ideas to drive the narrative.

A gay-couple

getting married after 39 years of marriage, George (Molina) loses his job as a

composer at a church for officially coming out, which forces him and husband Ben (Lithgow) out of their New York apartment. Ben rooms with his nephew’s family, George (Molina) with young gay

neighbors.

Love is Strange encompasses many stories

and subplots without ever feeling over-stuffed: Kate (Marisa Tomei) and Joey

(Charlie Tahan) play their annoyance at George's intrusion very well, as we see them

undergoing their own crises of identity, perhaps the intensity of their situations is too much to bear.

How they relate to a man that is old and not as sharp as he once was, unable to detect social cues, selfish and unaware as old age can make some? Molina's experiences are a bit more comical as he learns his neighbors’ party lifestyle doesn't quite mesh with his own.

How they relate to a man that is old and not as sharp as he once was, unable to detect social cues, selfish and unaware as old age can make some? Molina's experiences are a bit more comical as he learns his neighbors’ party lifestyle doesn't quite mesh with his own.

Contained

within the space and plot machinations of the film, is an allegory for the

inevitable separation that occurs when one partner leaves the other. Is it

possible to find your happiness apart from the person you’ve shared your life

with, to paint or compose with the same drive, to live fully and happily? The

film grapples with impermanence as an inevitable fact of growing older: Sachs

uses every character, from Tomei’s to Molina’s, to effectively explore his themes.

Love is Strange is about what it means

to love your friends, your family and your partner, and explores the various

strange forms this love might take. It is

the type of movie that is hardly made anymore but needs to be.

7.) Selma

Ava

Duvernay’s Selma is an ambitious work

of filmmaking, tackling the Selma to Montgomery marches with not only the

intention of chronicling but with exploring, as well, the various the personalities who made

it happen: Amelia Boynton, John Lewis, Annie Lee Cooper, Diane Nash, James

Bevel and many others, balancing the intimate with the grand, the political

with the personal.

This

a movie that explores the various meanings behind "coming together". Lyndon B.

Johnson is not passionate about passing the Voting Rights Act of 1965 until he

sees the police beating the protesters on his television screen. SNCC (Student

Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) and SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership

Conference) struggle against each other, until they realize victory is only won

if they stand tall side by side. Coretta King, marginalized in the household by

MLK's protectiveness, instead emerges herself by the end as a triumphant voice for

racial injustice. Duvernay casts an eye not only on the cruel beatings and

gassing on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, but on quiet moments, opening on King

(Oyelowo) adjusting a necktie, showing us his sorrows and

anxieties in a jail cell, his comforting demeanor to the grief-stricken father of Andrew Young,

explaining to Coretta with conviction that he loves her deeply.

Ava

Duvernay avoids the stuffiness of most period dramas. These are real people,

figures we can recognize, heroes with flaws and temperaments and anxieties. Selma inspires you by faithfully

chronicling this crucial chapter of the civil rights movement, by giving racist

villains such as George Wallace and Jim Clark their due indictment yet never

letting them descend into caricature. By proving that the ultimate enacters of change are ordinary people, not god-like heroes, and by showing us what is at stake

when we don’t participate in the political process, Selma takes deliberate pains to remind us that history is not best left in the past, but must continually be dealt with.

She never lets itself become too comfortable with standard story-telling, creates fascinating juxtapositions between King’s political activism and King’s home-life, balances the atmospheric with the humanistic and invites our audience to remember history and recreate it once more.

She never lets itself become too comfortable with standard story-telling, creates fascinating juxtapositions between King’s political activism and King’s home-life, balances the atmospheric with the humanistic and invites our audience to remember history and recreate it once more.

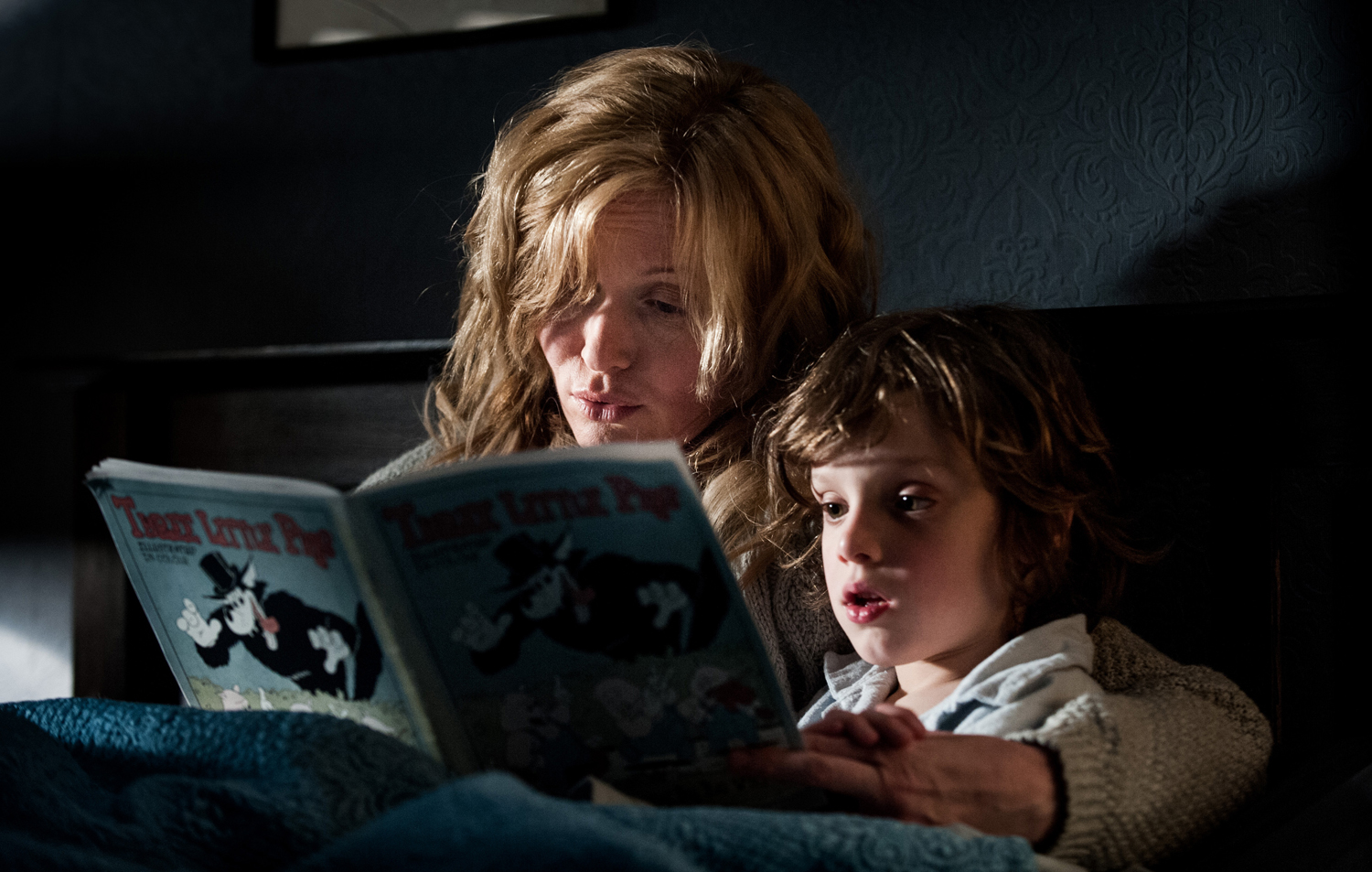

6.) The Babadook

It’s no

secret: horror films consistently rank among the weakest genre-films being made

today. Repetitive formulas, cheap thrills and over-worked folklore make the

medium hit-or-miss, with misses far more common than hits (and even then...).

Famed directors, from Kubrick and Hitchcock to Polanski and DePalma, have given

us the gold standards of the horror genre, works of art as well as works of

horror, and they've been long gone. Horror moviemaking also happens to be a

grossly male-dominated world, as is typical in Hollywood – but, in one of the

best surprises of the year, Jennifer Kent outdoes her male counterparts

with her debut feature, The Babadook. Unlike contemporary

hits Insidious or The Conjuring, this film

dares to embrace the banal conventions of horror to create something unique

and truly meaningful, an homage to its predecessors as well as a

(finally!) truly feminist and humanistic interpretation of the genre.

The

unsettling suspense of the film builds to the last thirty minutes, in which

Amelia’s confrontation with the Babadook rips your heart out. Because, while

entertaining us, Kent effortlessly draws out this touching narrative about a

mother fighting for control of her own mind. Davis gives one of the years best

performances, going from a deeply loving parent, to a possessed monster, to a

person desperate to gain back control. Sam can only helplessly watch as his

mother is devoured by the Babadook’s unrelenting grasp, as his mother confronts

the menacing and overwhelming monster.

5.) Two Days, One Night

Two Days, One Night is about the morals of cut-throat

capitalism and the will one must possess to survive in it. Marion Cotillard’s

quiet yet exhilarating performance anchors the Dardenne brother's sparse script and

hands-off directing style. It’s a documentary, almost, in its ability to bring

about these powerful moments through the most seemingly straightforward

conversations and moments. No music to set a mood, no elaborate cinematography,

no perceived artistry to be found, only the uncompromising style the Dardenne brothers usually approach their work with.

The plot

is deceptively straightforward - a woman is fired at the expense of employee

bonuses and confronts her co-workers to demand they stand with her in solidarity. It’s a stunning

morality play, but it is what underlies the story which makes Two Days, One Night such a transcending work

of art. She’s battling not only with those who want to keep their bonuses and

see her gone, but with her depression as well, a debilitating self-loathing

that sees itself realized when her boss informs her she is no longer needed.

“It’s always darkest before the dawn,” the clichéd quip goes, and Sandra –

after two weeks of barely recovering from a nervous breakdown, on hearing this

terrible news – must fend off the encroaching

dark clouds of depression and self-loafing to keep herself, her relationship and her family afloat.

If the social structures of the solar panel

company crumble faced with this ethical dilemma, it is simply the

fascinating backdrop of an extraordinary odyssey undergone by 2014’s most

complex and fascinating heroine. (I explore her complexity in my review: check it out!) The Dardenne’s have fashioned one of the best

movies of the year: Sandra’s story is our story.

4.) Leviathan

God is

everywhere, God is omniscient, God is unrelenting. But what God does each of us

worship? The characters in Andrey Zvyaginstev’s Leviathan are looking for a sign of God, which they maybe hope to see in the presence of

whale; this whale is a metaphor for a hope that never comes. We only see colossal bones, littered near the ocean, chalk white

and eerily cavernous. The small coastal Russian town our characters inhabit is

isolated and scenic, filled with humble men and women, many whom have grown up

together, working filthy jobs, whose sweet tonic is vodka (everyone drinks a lot in this!), who pride themselves on sticking together.

Roman

Madyanov is a revelation as Mayor Vadim Shelevyat, a character desperate for

power and respect. A portrait of Putin hangs menacingly as a reminder of the

powerful state. Throughout, we watch him converse with the priests, justify his

actions to evict Kolia and threaten his best friend with death, theorize about God’s power and his own. He is at once a monster and a

pawn, an arbiter of control as well as a small cog in a larger machine of Russia’s

corrupt political machine.

Leviathan draws from Dosteovsky and the

Bible, Kafka and Hobbes, Coppola and Shakespeare, but its uniquely immersive

and suffocating and contemporary. The Russian-Orthodox effigies that haunt the

film are extensions of governmental power – indeed, the grand theme of this

film is that religion and politics are inseparable and all-encompassing; Phillip Glass’s score punctures into us by the end, the shot of the waves crashing have us gasping for air, for a reprieve, but there isn't one offered to us. Leviathan is an indictment of these

superior powers that push us down and herald our suffering. It's the years most thoughtful film, and - man - does it pack a punch.

3.) Mr. Turner

“I believe

you to be a man of great spirit and fine feeling,” Sophia Booth (played

immaculately by Marion Bailey) tells Mr. Turner, the mysterious guest who

frequents her Margate-inn. Indeed, Mike Leigh’s Mr.

Turner is both a spiritual and emotional journey about a man hopelessly

searching for the many meanings and forms art takes in one’s life. In 19th

Century London, a time when paintings are being mainly valued as commerce and

commodities (aren't they still?), JMW Turner strives for artistic purity and integrity.

Throughout

the film, Mr. Turner, a heralded visual artist, must deal with his art becoming politicized and debated by wealthy buyers (I think of the HILARIOUS John Ruskin, who had me in tears) and mocked

and ridiculed by the general public. Timothy Spall’s insanely hilarious and

heartbreaking performance betrays vulnerability and bitterness, artistic drive

and sexual repression, anchors Leigh’s own vision of a world seen through the

eyes and the heart of an artist.

The idea

of JMW Turner, an artist ahead of his time yet intrinsically bound to his era, a

man of great flaws and deep existential anguish, is felt not only in Spall’s

brilliant performance but in the colorful tableaux’s framed by cinematographer

Dick Pope and in the quaint vignettes Leigh’s script gives us. Whether having us stare in disgust as he fucks his vulnerable servant on a bookcase or stare in awe of his peculiar genius as he splatters red paint on his work, Leigh invites the viewer into the moral and physical of 19th London, never

raising judgments against Mr. Turner or the ignorant world that surrounds.

Mike Leigh’s Mr. Turner explores JMW

Turner’s artistic temperament while heralding a unique cinematic language all

its own, as visionary and heart-breakingly enigmatic as the multifaceted main

character who mans the movie’s helm.

2.) The Grand Budapest Hotel

Wes

Anderson’s best film to date, The Grand

Budapest Hotel is a truly original and

groundbreaking piece of filmmaking, bringing together many actors from the

Anderson-arsenal to deliver a ravishing tale about the rise and decline of the

mythic Grand Budapest Hotel.

If

this movie should be characterized with one all-telling adjective, it’s nostalgia: the story-within-a-story-within-a-story

suggests as much. The quixotic, melancholic fable is told by former lobby boy

Zero Moustafa. It is a recollection of his days a lobby boy in the

Grand Budapest Hotel, a relic of an old world much like its dedicated concierge

M. Gustave (Ralph Fiennes) who takes the orphan under his wing.

When

Madame Céline Villeneuve "Madame D" Desgoffe und Taxis (Tilda

Swinton) dies and M. Gustave inherits her treasured ‘Boy with Apple,’ a series

of events ensues putting M. Gustav and his dedicated lobby boy Zero into

conflict with both the Taxis family and the Nazis. Admist the trouble, Zero

falls in love with the baker Agatha, Gustave chips his way out of a jail

Alcatraz-style and Jopling stalks them with the ferocity of a savage detective.

It

brings together many classic plot lines and tropes to weave a tale not only of

grand artistry but great fun as well. European architecture, old-world customs, slap-stick

humor, Edgar Allen Poe, gourmet confections, gangster-like bullet

slinging, Alcatraz jail escapes and family-inheritance trysts: Anderson’s masterpiece The Grand Budapest

Hotel has it all. It’s escapist and fantastical movie-making at its oh-so best!

1.) Boyhood

Boyhood has already received

unanimous praise and critical treatment so I won’t yell at deaf ears. I’ll only

say it’s the year’s best for a reason. It’s not only an incredible achievement

and admirable committed work on behalf of Richard Linklater and his acting

ensemble, but it’s a truly original, a time capsule. Its an authentic look

at coming-of-age, one that struck me particularly because of how much I saw

myself in Mason. It’s effortless and genuine and a lot of fun. I saw my life through

Mason’s, and it was a cathartic experience to see him grow-up before my own

eyes. Unequivocally, 2014’s best film. A masterpiece on so many levels.